New 1-Minute Video Script

Look up at this tall white pine. Its shape tells a story of the land around it. In the mid-1800s, this hillside was an open sheep pasture—part of Maine’s “Sheep Fever” era, when farmers cleared vast tracts for grazing. The stone wall nearby marked the pasture’s edge.

When the pasture was abandoned around 1850, sunlight-loving pines like this one were among the first to return. The tree’s wide-spreading limbs show that it grew in the open, free from competition. Its multiple trunks reveal another clue: early attacks by the white pine weevil, an insect that targets young trees exposed to full sun.

Pause here and imagine the transformation—once open grass and grazing sheep, now a quiet forest reclaiming its ground. This “pasture pine” stands as a living witness to how quickly nature heals and how the forest remembers its past.

Pasture Pine

More about Pasture Pines

White Pine Weevil

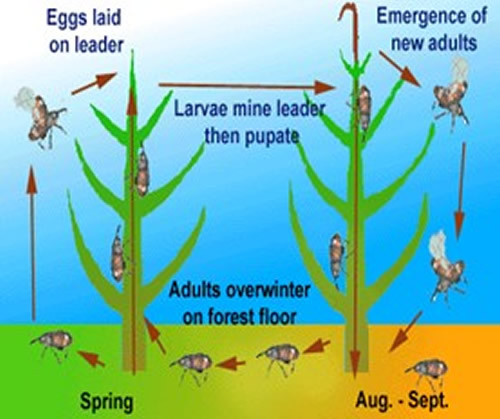

The white pine weevil is a native to Maine. It targets the terminal leader—the topmost shoot—of the tree, leading to deformities such as the multiple trunks that you see here. In early spring, adult weevils become active, feeding and laying eggs in the bark of the previous year’s leader. Larvae hatch and tunnel downward, girdling and killing the leader. By mid-July, new adults emerge, feed briefly, and then overwinter in ground litter at the tree’s base.

Dating Trees

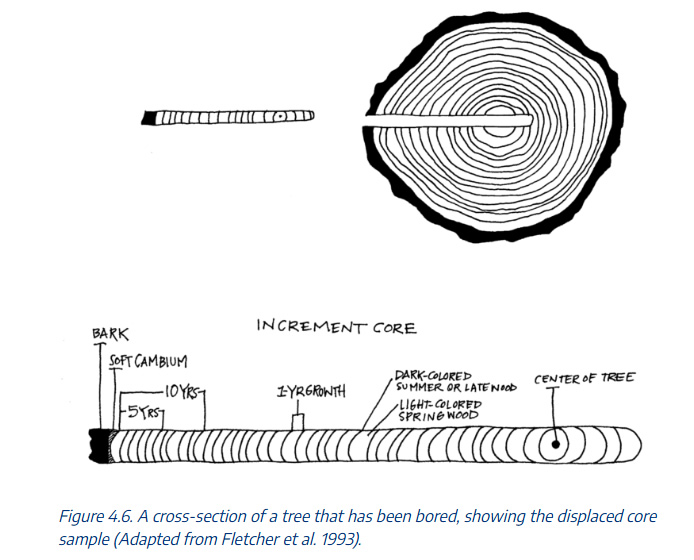

A simple method for dating a tree is to measure the circumference of the trunk at breast height and then use a formula to calculate its age. However, pasture pines with multiple trunks can often overstate the trees age using this method. These secondary trunks can distort the results because the tree produces larger rings at the base to help support the greater mass.

The best method is to count the rings. Rather than cutting down the tree to see the rings, an increment borer can extract a core sample without damaging the living tree.

Studying the location and age of the pine trees will help determine the size and range of the pastureland that once was here.

Combining The Evidence

Notice the area surrounding this pasture pine. All the nearby trees are much younger. Also, consider that the tree has broad branches and is located near the pasture’s boundary, as defined by the stone wall. Taking all this together, It means that this was probably one of the first trees to colonize the area when the pasture was abandoned. Sheep fever began in the early 1800’s when the first Marino sheep were brought to Warren Maine. It ended when the price of wool collapsed in the mid-1800’s, triggered by the restoration of cotton production after the Civil War and by competition from midwest farmers, who could graze sheep on more productive land.

At the Stone Fence stop there is more detailed information about Marino sheep and how they were raised here.

Crowd Sourcing: Your Thoughts

We welcome your insights. Please complete this form with your ideas. This will help use improve our educational mission!

Pine Dating and Mapping Project:

The purpose of this project is to determine the age and location of pine trees. In a forest like this one, which has been periodically disturbed by humans over the centuries, we can determine landscape changed by studying how pine trees have proliferated. Pine trees typically are among the first to colonize open spaces. Knowing when a pine tree sprouted helps reveal when a pasture of clear cut area was abandoned. With a detailed map we can visualize boundaries and timing of changes to the landscape.

Support all our projects with a donation!